Why the Bofors scandal must never be forgotten

The first sensational revelation in the Bofors scandal was made on 16 April 1987, more than 25 years ago, when the Swedish National Radio reported that bribes had been paid to top Indian politicians to secure the howitzer gun contract.

The median age in India is 26 years, which means that about half of India grew up in a post-Bofors scandal era, and may not know (or care for) the intricate details of what the case was all about.

And since, even after 25 years, none of the principal beneficiaries of the illegal payoffs have been convicted, and not a single paisa of the Rs 64 crore has been recovered (and in fact more money has been spent on investigations than the original payoffs), it may seem tempting for those with short attention spans to ask: What’s the big deal? Why are we still talking about it?

It’s precisely that constituency of apologists for monumental corruption that Salman Khurshid addresses when he argues that there is no need to reopen the closed chapter of the Bofors case.

But there are compelling reasons to argue that Bofors, which has become a living, breathing metaphor for corruption in high places in India, should never be forgotten. Even if the Rs 64 crore payoffs seem like a pittance compared to the monumental scale of corruption scandals today, Bofors will – and ought to — remain as a permanent reminder of just how deep the rot runs in our polity, and of the enormous levers that people in power have to scuttle investigation.

It shows up how from the Prime Minister downward, politicians were given to openly lying – despite clinching evidence to the contrary – because they had their own interests to protect.

It also shows up an entire ecosystem of corruption, facilitated by politicians, bureaucrats and arms manufacturers and their agents, which compromised every institution of our democracy – from parliament to the executive to the bureaucracy to the investigative agencies to even the judiciary.

That is why despite the strenuous efforts of well-meaning investigators – both in India and Sweden – to expose the scandal, and the exertions of some sterling investigative journalists who ferreted out and presented the most extensive documentation of clandestine Swiss bank payments, the trail ran cold.

Indeed, if Sten Lindstrom, the former head of the Swedish police who had led the investigation in Sweden into the Bofors deal, had not identified himself earlier this week as the “whistleblower” who had made available to The Hindu’s journalists some hundreds of top-secret documents that traced the payoffs and blew the lid off the scandal, perhaps the case would have long been forgotten.

In his interview to Chitra Subramaniam-Duella (The Hindu journalist to whom he handed over the documents in 1988), Lindstrom validated what had been known for long: that, contrary to popular belief, Rajiv Gandhi himself did not receive any payoffs in the deal, but that Italian businessman Ottavio Quattrocchi, a family friend of Rajiv and Sonia Gandhi, did receive commissions.

Lindstrom also confirmed that Rajiv Gandhi knew of and was complicit in the elaborate cover-up that his government orchestrated to protect Quattrocchi.

Quattrocchi’s connections to India date back to 1964, four years before Rajiv Gandhi’s marriage to Sonia. From then, until 1993, when a Swiss cantonal court revealed Quattrocchi and his wife Maria to be the beneficiaries of a shell company account to which Bofors payoffs had been made, he wielded enormous clout in Delhi’s power circuit, even during Indira Gandhi’s time. But it was during Rajiv Gandhi’s tenure as Prime Minister that Quattrocchi spread his wings – wielding enormous powers over Ministers and top bureaucrats.

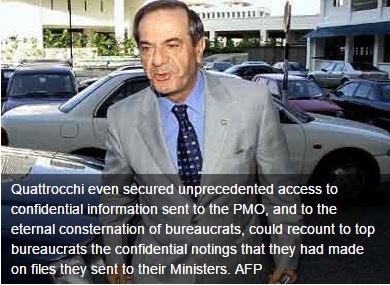

Quattrocchi even secured unprecedented access to confidential information sent to the Prime Minister’s Office, and to the eternal consternation of bureaucrats, could recount to top bureaucrats the confidential notings that they had made on files they sent to their Ministers.

But it was his role in the Bofors gun deal that established far and away his enormous clout in Delhi’s power circles. AE Services, the shell company that Quattrocchi operated, was a late entrant to the Bofors deal. Bofors at that time had existing contractual arrangements (going back several years, even decades) with two strands of companies in which arms agent Win Chadha and the Hinduja brothers – GP Hinduja and Srichand Hinduja – had interests.

But AE Services, Quattrocchi’s shadowy outfit, cut in at the last minute, on 15 November 1985; and under the terms of Bofors’ contract with the company, AE Services was entitled to a commission only if the Bofors deal with India was signed before 31 March 1986. It was a measure of the supreme confidence that Quattrocchi had and was able to communicate to Bofors, that such a contract was signed at all. Tellingly, the Bofors deal was signed on 24 March 1986, a week short of the deadline.

Since then, it’s been a story of massive cover-up and deception. And although the Opposition parties extracted much political mileage from it – VP Singh campaigned on the anti-corruption platform in 1989 and won – even they were less than successful in establishing a strong enough case even when they were in power. As Subramanian Swamy’s revelation to Firstpost made clear, even the NDA government was less than enthusiastic about getting at the truth in the case, going so far as to prevent Lindstrom from interrogating Sonia Gandhi.

The Opposition today is demanding that the case be reopened for investigation. The heart concurs with the demand, since there’s still a bit of residual justice to be rendered. But the head reasons – on the basis of 25 years’ experience – that nothing may come of it if there is no earnestness about seeking the truth.

Yet the issue assumes importance in the context of the debate over the establishment of an independent anti-corruption agency. When the point was made during the campaign for an effective Lokpal, it was mocked as paving the way for a supercop agency. But such an agency may have offered the best chance of exposing the scandal.

The cynic in us may say that such an agency will never come up for precisely that reason; yet, we have to hope that it will. We may be able to do nothing about our monumentally corrupt past, even when it led right up to the Prime Minister’s Office, but we ought to shape our destiny going forward at least. And in that endeavour, the Bofors case, with all its failings, is the lodestar that should guide us towards establishing institutions that genuinely combat corruption.

You May Be Interested IN