Geometry and symmetry in Indian architecture

ELLORA CAVES, AURANGABAD, MAHARASHTRA

The famous rock-cut caves of Ellora depict the Hindu, Buddhist and Jain faiths, and were built between the 5th and 8th centuries. Though the carvings in their entirety are a sight to behold, when talking about geometrical and symmetrical patterns, it's mainly the carvings of the Buddhist caves that come to mind. Of the 34 caves, only 12 are Buddhist. The ceilings of these caves have been carved and often painted with geometrical designs reminiscent of the mandalas, while the walls and pillars depict the life of Budhha.

MATHERAN, MAHARASHTRA

This is more of a visual delight for photographers. The colourful staircases provide great dimension to an otherwise dull frame and — to be fair — keep your eyes open for such serendipitous occasions across the country.

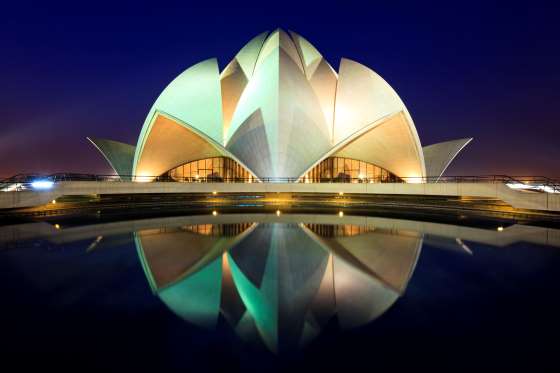

LOTUS TEMPLE, DELHI

The architectural style of this house of worship is called Expressionist Architecture. Completed in 1986, the Lotus Temple was designed by Fariborz Sahba, who wanted to bring out the concepts of purity, simplicity and freshness of the Baha'i faith in his design. The leaves' structure, number and inward-outward slants can all be defined in geaometrical shapes of spheres, cylinders, toroids and cones.

LOTUS TEMPLE, DELHI

There are three sets of leaves/petals — the outermost set of nine petals, called the 'entrance leaves', open outwards; the next set of nine petals, called the 'outer leaves', point inwards; and the third set of nine 'inner leaves' petals appear to be partly closed — giving the impression of a slightly opened bud.

HOYSALA TEMPLE, BELAVADI, KARNATAKA

The Veera Narayana temple was built during the rule of the Hoysala Empire around the 13th century, and the style of architecture that was prevalent at the time is called Hoysala as well. Most Hoysala temples are ekakuta, dvikuta or trikuta — that is, one, two or three shrines. And in temples with multiple shrines, all essential parts were duplicated for symmetry and balance. Many of the ceiling panels are carved with geometric patterns, while some others would feature celestial figures and warriors in different postures. In general, the temple architecture is open, symmetry-driven with variations of squares and circles.

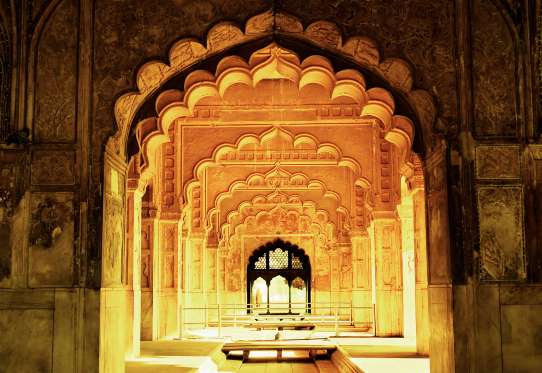

RED FORT, NEW DELHI

The red sandstone structure complex is built as an irregular octagon. Constructed in 1648, the fort was the regal residence for nearly 200 years. The architecture is reflective of the later Mughal style that was more ornate and innovative. The Red Fort, in this list, is an example of assymetrical and symmetrical styles coming together in one holistic example. While the walls and overall layout of the fort are asymmetrical, the smaller palaces inside, such as the Diwan-e-Aam, are striking, beautifully symmetrical, with open sides and front. The Rang Mahal — which is a small chamber inlaid with fine mirror-work — boasts of some stunning arabesques and geometrical patterns on the ceiling and upper walls.

ISKCON TEMPLE, VRINDAVAN, UTTAR PRADESH

The Sri Krishna-Balaram Mandir is of the main ISKCON (International Society for Krishna Consciousness) temples across the world. Here one can find yet another example of the chequered courtyard.

CHAND BAORI, RAJASTHAN

Chand Baori, a stepwell in the Abhaneri village of Rajasthan, is one of the oldest stepwells in Rajasthan, and is considered to be among the biggest in the world. This gorgeous structure is 13 storeys deep, with double flight of steps lining it on three sides. The 3,500 narrow steps are arranged in perfect symmetry to the bottom of the well.

CHAND BAORI, RAJASTHAN

Built during the 8th and 9th centuries, the geometrical pattern followed across the steps follow the same equilateral triangle pattern where a collection of three smaller triangles would make a bigger one, and so on and so forth. Other geometrical shapes that are easily visible are that of rhombus, diagonal criss-crossing lines. That's a lot of math for a structure that's over 1,000 years old and used to provide water to nearby villages.

BHOGA NANDEESHWARA TEMPLE, NANDI HILLS, KARNATAKA

The Bhoga Nandeeshwara Temple is dedicated to the Lord Shiva, and the original temple is said to be one of the state's oldest temples, dating back to the 9th century. It was later renovated in the Dravidian style of architecture. The temple is beautifully ornamented with monolithic stone pillars that give the impression of a very symmetrical structure. Though, when looking at lines, it's the water tank, the rock-cet steps and the colonnades around it that pop into one's mind. The colonnades are symmetrically surmounted by numerous stepped pyramidal towers of which the ones in the corners and the centres of each side are considerably larger than the rest.

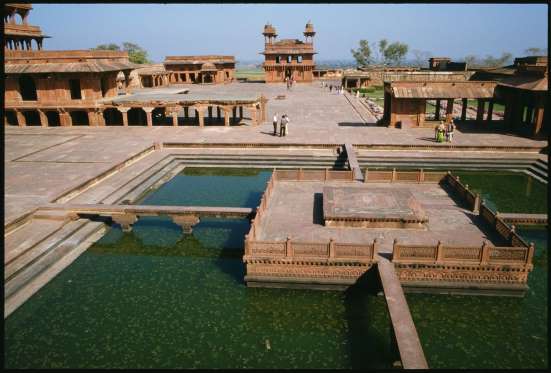

FATEHPUR SIKRI PALACE, UTTAR PRADESH

Fatehpur Sikri was founded in 1569 by the Mughal emperor Akbar, and served as the capital of the Mughal Empire from 1571 to 1585. The imperial palace complex consists of a number of independent pavilions arranged in formal geometry on a piece of level ground, a pattern derived from Arab and central Asian tent encampments. Of particular mention at the palace complex is the jali work, or stone-pierced screens with intricate geometrical designs on the Tomb of Salim Chisti as well as the inlay work of floral and geometrical patters in the Diwan-i-Khas. The complex still stands as one of the finest examples of Mughal architecture from Akbar's time.

HUMAYUN'S TOMB, DELHI

This 16th century tomb inspired the architecture of the Taj Mahal and other Mughal buildings, so no wonder it ranks extremely high on the scale of using geometrical patterns and symmetry while amalgamating Islamic cosmology in its own architecture. The burial technique used here — along with pietra dura, a marble and even stone inlay ornamentation in numerous geometrical and arabesque patterns, seen all around the façade — is an important legacy of the Indo-Islamic architecture. According to architects, the symmetrical and simple design on the exterior is in sharp contrast with the complex interior floor plan, of inner chambers, which is a square 'nine-fold plan'.

HUMAYUN'S TOMB, DELHI

Chamferred edges — cut away (a right-angled edge or corner) to make a symmetrical sloping edge — add to the overall symmetrical design of the mausoleum. Even the garden is highly geometrical, which is divided into four squares by paved walkways and two bisecting water channels that are meant to reflect the the four rivers that flow in Islamic paradise, or Jannat.

RANI KI VAV, PATAN, GUJARAT

This 11th century stepwell is an excellent example of Gujarat's subterranean architecture. It has been designed as an inverted temple with seven levels of stairs — each platform possessing a unique characteristic, whether it be the Dasavatara of Lord Vishnu, the Holy Trinity of Brahma-Vishnu-Mahesh or otherwise complex geometrical patterns. The columns have been strategically placed so that the idol of Vishnu lying atop Shesh Naag is visible from different angles. The repeated geometrical patterns gracefully meld with the floral and mythological motifs across the various levels of the memorial stepwell.

JANTAR MANTAR, DELHI

A collection of architectural astronomical instruments, built by Sawai Jai Singh II in the 18th century. It has 13 instruments that calculate the movement of time and celestial bodies. The observatory was completed in 1724. There are three major instruments — Samrat Yantra, the Jayaprakash, and the Misra Yantra (in pic), of which the Misra Yantra is made of five different instruments and is unique to the Delhi observatory. It is said to tell the observer when it is midday across various parts of the world. When it comes to the marriage of geometry and architecture in India, it is really very difficult to beat the Jantar Mantar!

JANTAR MANTAR, JAIPUR, RAJASTHAN

A collection of architectural astronomical instruments, also built by Sawai Jai Singh II, is one of the largest observatories of the world and has been modelled after the one in Delhi. It consists of 14 major geometric devices that measure time and can be used to predict eclipses. Each instrument has a particular function. Take, for instance, the Samrat Yantra — one of the largest in the milieu at height of 90 ft — is used to plot the time of the day depending on the play of light and shadow. Its face is angled at 27 degrees, which is the the latitude of Jaipur. The ingenuity of the king was in making the Jai Prakash yantra (in pic) that allowed — with minor modifications — people to even gauge the time of the night as well as the position of the stars and constellations. The Hindu Chhatri (small cupola) on top is used as a platform to calculate and predict eclipses and the arrival of monsoon. There are similar observatories in Mathura, Varanasi and Ujjain.

You May Be Interested IN